Weeknotes, JRF, Feb 7

I haven’t seen In the Mood for Love for 20 years, but had a long phone chat with my younger sister about it this week. Maggie Cheung’s outfits and pain, the deep, withholding loneliness of the script, the lingering camerawork, almost too on the nose but still works, the confidence of the set design and the transcendent hotness of Tony Leung smoking. Such a film.

I still love Hong Kong. Just finished The Honourable Schoolboy, which is partially set there. It reminded me that, for all of John le Carré’s brilliance, his descriptions of non-Western characters echo what I’d imagine after-work banter at the old Colonial Office sounded like. Urgh. Even less successful than Graham Greene. (A low bar.)

It was kind of a quiet week in general, which felt…nice?

The quality of my writing will inevitably suffer for my lack of rage, but you’re here now. Might as well read on.

Fun with procurement

Who doesn’t love procurement chat??

I’ve been sorting out some content design training and getting a research recruitment agency onboarded — fingers crossed! Ongoing huge thanks to Grace, Sallyanne and Patrick for helping me with this stuff.

I put together a draft of a brief for a procurement transformation discovery/alpha. Figured a lot of agencies have Strong Views on it, so sharpen your pitch-typing fingers, friends. It needs to go through a few different channels before it’s open for bids, but it’s the sort of thing that both needs doing and probably shouldn’t be done by an in-house team.

If they’re reasonably scoped, that Swiss-style neutrality is really useful for projects like this one. Lets agencies take in different perspectives and suggest ideas for how to do it in ways that meet (sometimes contradictory) user needs. The sort of project they do well and in-house teams find difficult, basically.

Relationship management things

(Tech, not therapy. This time.)

For the past few months, I’ve been working with Geoff (who runs “Tech and Change” in another part of the group) to bring together our teams to look at how JRF does relationship management. I know a lot of organisations have a historic divide between digital/design and IT/tech and I can see where it comes from. But I don’t think it makes sense.

Funny: I remember the GDS design and creative teams going to one of the (old?) Google offices in Victoria in…I want to say 2014? 2015?…and all of us being surprised that their tech and design teams didn’t actually work together. The air of smugness was strong when we left the building. Though I seem to remember being jealous of their snacks and fancy lobby.

The point is that it’s a dated divide and that snacks are important.

JRF already has a CRM, Dynamics365. A name that leans in to its corporate origins so heavily I can’t help but be impressed, and keep spelling it Dynamix365. Nobody (I think?) really wants to do a big migration to another one. But what does JRF need from a CRM? Who is it working for, and who isn’t getting what they need — from that, or from the other tools (cough, Excel, cough) JRF is using to manage external relationships? What options are there?

Less minimum viable product, and more minimum viable effort (with maximum impact ← pronounced in Big Andreessen-Horowitz Voice).

So Geoff and I have put together a brief. Hannah from my team, who is a marketing manager, and Steve from Geoff’s team, who is a Dynamics expert, are going to work on it a day a week for the next little while. Steve knows the current platform, and Hannah has done some thinking about what we need from it. I know other people in JRF have too, so no need to start from scratch, which is nice.

Culture bits

Hannah and Steve will be doing a lot of (supported!) learning by doing, which I’m hoping will be fun rather than terrifying. ← great management tactics there, Ella. We all believe we’re going to be better than our parents, hmmm?

Gave some feeding back and strategic direction for prototypes that went to user testing for the sprint I mentioned last week.

I had the strategic direction bit of that sentence in scare quotes first, because the need to justify something as “strategic” to give it weight is giggle-inducing nonsense. Reminds me of Ade Adewunmi (an actually strategic person) saying “You know what we don’t need any more of here? Strategic thinkers”, which always makes me laugh. Plus, most people who describe themselves as “strategists” are either not, or have no marketable skills beyond confidence. (Obviously, I like to think of myself as exempt from this. I would, though. )

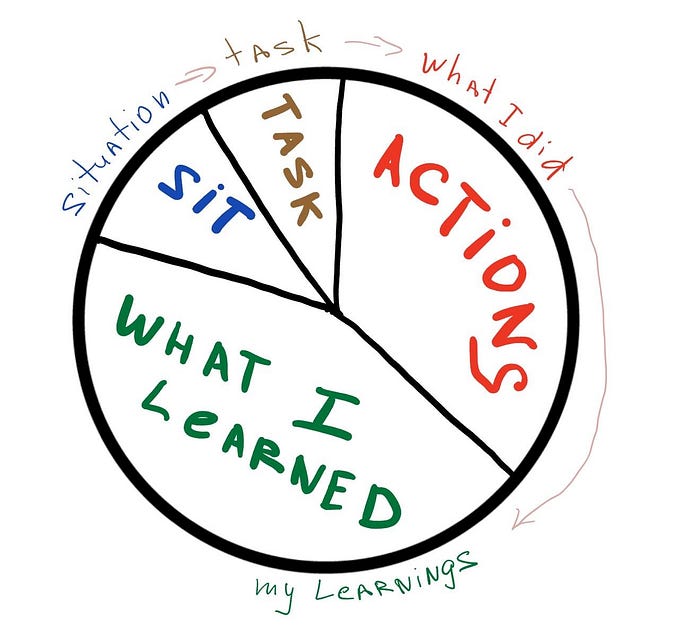

On that point, this was great:

In light of my lukewarm, vaguely pub-ranty takes about theory and practice, I’m trying to encourage a culture where it’s OK to “just try” some stuff and see what happens. It’s a bit of a culture shift for the teams, and having Daniel and Holly’s support in that is invaluable. Am hoping talking to external users every two weeks will help with that, and be part of creating a culture where it’s entirely fine to have works in progress and ideas that aren’t quite right.

If not, I’ll have to develop a more elaborate theory, I guess.

Schrödinger’s timesheets

Look, everyone hates timesheets.

But in strat comms, Ryan and I were chatting about needing a better view of how people use their time. Prioritising is my job; making things happen is Ryan’s. If you’re running a team, and you don’t know how people are using their time, you don’t know why or when they’re stressed and how you can help. That’s extra true remotely. Plus, it makes it almost impossible to explain to in-house clients why you’re saying no to some things and yes to others.

How do you both have timesheets, and not have to do timesheets?

Ryan’s put together a lovely, colour-coded “finger in the air” spreadsheet of what people have been doing and think they’re going to be doing. Annoyingly, the project management software we’re using doesn’t do this automatically, so he used Excel for it.

It doesn’t need to be all that accurate — we’re not billing external clients — just right enough that to let the team be transparent about how they’re working. Will see how it goes. (I’d put it here, but it’s on my work laptop and I don’t open it on weekends.)

Content strategy thinking out loud

I liked the blog posts Paul pulled together (the technical term for interviewed and edited) the other week, with and about people living in poverty.

One of the things I’m interested in for the new website is how (or if?) to bring that content onto the main publishing platform.

Blog posts and posts about events are an increasing part of traffic to JRF.org.uk. Which would seem like a good thing, and it sort of is. But working with people with lived experience of poverty is supposed to be a central part of what JRF does. Hosting their stories as a series of blog posts, while completely the right thing to do under the site’s current structure, doesn’t sit right with me.

I’m increasingly dubious about the value of dividing professional content into “reports” and “blogs”. The first person-ness of blogging just isn’t there with most professional content. (Not only because of editing and ghostwriting, but also because of that.) And if that intimacy and episodic unfolding over time isn’t there, why isn’t it just…web publishing?

I think the increase in traffic to our main JRF blog has to do with the content itself, not the content type. And blog posts don’t strike me as the best possible content type for these stories. They’re powerful, and beautifully shaped by Paul — what are better ways of showcasing them? A thing to test for the future.

Who is the “we”?

My brother-in-law John, Mark and I had a fun email exchange this week. It started with talking about the Zuboff article in the NYT, and why I think she’s overrated and under-fact-checked. And why Mark thinks that people our age and younger are suspicious of the media. (Look, if you know Mark you know that’s not what he actually said. But I need to work again, and some of my work is media-adjacent.)

(Then Lee Vinzel published this, You’re Doing It Wrong: Notes on Criticism and Technology Hype | by Lee Vinsel | Feb, 2021 | Medium which I’ll just be sending to people instead rather than bother formulating arguments myself).

Because it’s lockdown and there’s nothing else to do, this amazing piece captures some of the roots of that mistrust really well among other things, including a fair teardown of a Mangan column in The Guardian. I’ll be totally fine with you not reading to the end of my post and reading it instead, tbh.):

The lesson is this: if you’re a member of a minority, and the fatal disease you contract is spread through sexual contact, you only have to wait 40 years, have 35 million die in skeletal agony, have another pandemic affect everyone and a once-in-a-generation dramatist to devote five hours of primetime TV to your plight in order for lucky people — and that’s all they are — to fully, you know, care.

Look, I’m as white and middle class and middleaged as the writers who use it. I like to think I’m better than Lucy Mangan, the voice of basic North London, but we share a lot of identity markers. And that “we” in her review is awful for all of the reasons that Strudwick outlines. But it’s really common in English progressive circles, and it shouldn’t be. I’m not part of that “we”, and I don’t want to be.

Editors, do your duty. Get rid, or at least challenge it.

It’s also one of those insidious things brands do to give a false sense of familiarity, or companies do to pretend that they’re a nice, communal place to work. Fun fact: almost never true.

Or couples do to present a united, nuclear family front. Again, almost never true. (I mean, have you met a couple that only speaks of themselves as “we” and who aren’t pretty miserable? I haven’t.)

I still love that the GOV.UK style guide asks writers to be careful about it. Though am I right to remember that the guidance used to be spikier and meaner? It’s how it felt at the time.

So please, people. Just banish it unless it’s confusing not to. Or if writing for an explicitly unified organisation, where people agree to it.

Or unless you’re Julie Otsuka, because her use of the first person plural in The Buddha in the Attic was not only excellent and (ignoring the orientalising terms used by most of the reviewers at the time — white reviewers need to stop describing writing by Asian/Asian American authors as “delicate”, ) deeply, stabbingly political. This was one of the better reviews, if you missed it at the time:

End bits

Jay’s take on the Handforth Council debacle was great.

Thought that The White Tiger (film) was terrible. All the reviews I’ve read have been gushing, other than a good one in AVClub.

Helpfully, it talks about how the films is all exposition and reviewed as a corrective to Slumdog Millionaire (did this need correcting? Did viewers really believe it was anything but a fairy tale? Are we offering fact checks on Disney movies and The Crown now? Wait…), drowning in voiceovers and predictability.

Also, I read a bunch of interviews with Adiga from around the time he won the Booker (2008? 2009?) to see if I was getting it wrong. But the ways he insists on his inalienable right as an upperclass person to write as a poor person reads as something from a very different era of literature and theory, where it was received as a novelty in British publishing to have Indian writers write about India. He cites both Dickens and Zola as sources of inspiration. I get that: Dickens is unfashionable, but I love him, and Therese Raquin a coldhearted masterpiece. But both Dickens and Zola experienced poverty growing up, which feels central to the power of their writing — and it’s a strange thing to see Adiga’s interlocutors fail to call him on that. Again: editors, do your duty. And don’t bother to see the film, even if Priyanka Chopra is v pretty in it.

The new FKA Twigs video is something I’ll be thinking about for a long time.

Kara Walker’s always great, and I appreciate the opportunism of shooting in the Tate turbine hall when it’s closed. Poignant, pointed and brilliant.